Backwoodsman’s recent school report for photography has read “Has worked hard but could do better” or possibly “He could have been a good photographer but he lacked focus.” Backwoodsman loves a daft joke; one of his favourites from the distant past can be enjoyed here. As the main point of the site is the sharing of nice images, the recent history of underachievement has not encouraged him to post. Perhaps it is time to start again.

Backwoodsman’s “Jewels of North Glasgow” run often takes place on Sunday mornings. It first hits the Forth and Clyde Canal at the large basin just below Speirs Wharf. Of this area, the Inland Waterways Association writes “Although the Glasgow Arm to Speirs Wharf was re-opened as part of the Millennium Link project, the basins at Port Dundas were not. A £5,700,000 project, planned by BW (British Waterways) Scotland and Glasgow City Council, to reconnect Port Dundas with the rest of the canal was completed and formally reopened in September 2006… However, the new lock…has not been available for public use since then, and the potential to revitalise the area originally envisaged has yet to be realised.”

It is hard to imagine what was originally envisaged in the way of revitalisation, and what justified dropping £6M on such a venture; happily, apart from the insistent throb of the motorway, the basin remains a quiet place, undisturbed by narrow boats or paddleboarders (Backwoodsman thinks them foolish).

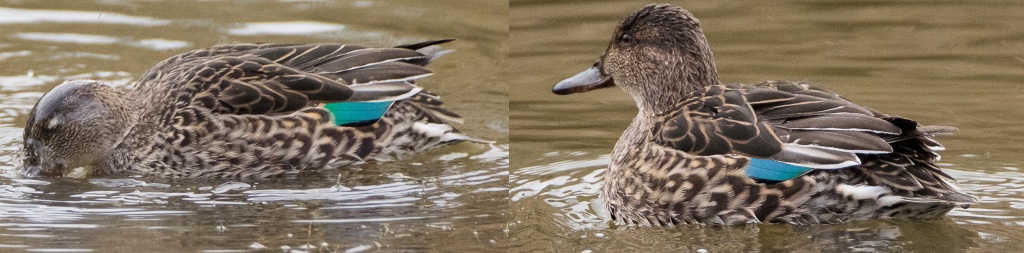

A dozen or so Tufted Duck came to the lower basin in the autumn and have wintered there for the first time in Backwoodsman’s memory. They have neither strayed up onto the Speirs Wharf stretch, nor eastward to Pinkston Basin. Tufted Duck seem to be very selective over which parts of the canal they populate and Backwoodsman wonders if a food source drives the selectivity. Tufted Duck also turn up regularly on the Westerton to Drumchapel section of the Main Branch as it heads down to the Clyde at Bowling, but Backwoodsman has rarely seen them between Maryhill and the city centre. The RSPB book states that they eat freshwater shrimp, caddis larvae and pondweed – the latter food source is abundant throughout the entire length of the canal (alas, rendering it unfishable).

Tufted Duck also eat Zebra mussel and Backwoodsman wonders if there are local infestations of this invasive species in the canal, though this is a wild speculation. The risk posed to Scottish waters by this tiny bivalve has been posited, but there there is ambiguity as to its presence or not. Backwoodsman should probably do some citizen science and see if any Zebra mussels can be collected but you never know what you’ll haul up from the bottom of the Forth and Clyde Canal City Branch. The odd body turns up in the canal from time to time. We’ll leave the citizen science job to the magnet fishermen.

Anyway, it’s been lovely to see the Tufties throughout the winter; the group has dispersed now, possibly to better breeding sites. It would be delightful to see ducklings but the chances are that the local gulls would see them first. Other good places to see Tufties around Glasgow include Hogganfield and Frankfield Lochs, both shallow and weedy bodies of water.

The “Jewels of North Glasgow” run heads past Pinkston Basin, taking in the Pear trees and the towpath Cowslips, which are now in bloom, crosses Pinkston Road and follows the railway cutting along the edge of the North Bridge estate, heading towards Fountainwell Road and Sighthill Cemetery. Wood Anemones here, planted beneath shrubs including a Corylopsis pauciflora and then more Cowslips.

It is a fragrant route, what with McGhees Bakery and Biffa Waste Management just across the railway, and usually good for corvids and lots of Starlings. The route turns right to follow Springburn Road, where someone must have had every young offender in Scotland on their knees planting thousands of Primula denticulata. Quite right! As one of Backwoodsman’s academic colleagues in Birmingham used to say, “they can be put to work.”

Right again past the car dealership and onto the main part of the estate passing the Rusty Bridge. There appears to be an interference pattern in this image!

The BBC recently ran a feature on this splendid installation and they managed to find all four people who use the new bridge to get across the M8. One of then gushed: “”I park here for free and I just commute to university,” she said. “It’s so much easier and better than paying for parking in the centre.”” Do you indeed! Students driving to their lectures at a university located next to a major bus station and five minutes from a rail terminus and the Subway. Backwoodsman guesses that’s the active transport the council is so keen on.

There are some splendid cherry trees atop the hill by the bridge; the sakura season has been thwarted in Glasgow this year, literally nipped in the bud, so some trees in full bloom are a highlight.

From there, it’s back to Pinkston and then home, greeting the Tufties in passing.

We have other Aythya species in the UK and Backwoodsman has been pleased to find Pochard (A. ferina) on Hogganfield Loch (male then female) and Scaup (A. marila) (male then female) at Slimbridge. Backwoodsman thinks the three species make a presentable bundle. Please enjoy the vermiculated feathers of the drakes and the splendid textures of the ducks.

Backwoodsman hopes to post more regularly again from now on.